missionary position |

Former Cop and Call Girl

|

|

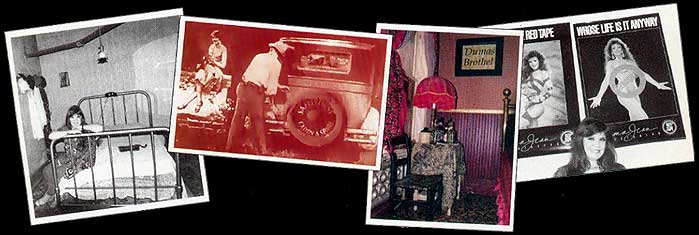

I was born and raised in a fundamentalist Baptist family. I was enrolled in Philadelphia College for the Bible. "I was going to be a missionary," Almodovar says then realizes and she giggles, "I still sort of am if you want to look at the reality of what I do." She is an author, lecturer, sculptor, human rights activist, a former candidate for Lieutenant Governor of California, an expolicewoman, and a whore. Yes, and cocksure of it. Almodovar joined the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) as a civilian traffic officer in 1972. Disillusioned by the corruption she witnessed, Almodovar left the force after three years. She became a part-time Beverly Hills call girl, all the while writing a book about her experiences with the LAPD. In 1983, her manuscript was confiscated by the police and she was arrested for pandering. Almodovar was incarcerated for a psychiatric evaluation, spending fifty days in isolation. In 1985, the court ruled that the mandatory three to six year prison sentence was cruel and unusual punishment—instead, she was sentenced to three years probation. Later that year, Los Angeles District Attorney Ira Reiner appealed her sentence, arguing that her offense "was worse than rape or robbery" and further, that she compounded her "crime" by writing a book that would promote "disrespect for law and order." After several years of tangled appeals, Almodovar was resentenced to three years in prison, serving over seventeen months as an inmate of the California Institute for Women and California Rehab Center. She was released with three years parole, and released from parole on January 1990. Almodovar had lost seven years of her life. Cop to Call Girl was finally published by Simon and Schuster in 1993. Almodovar is executive director for the Los Angeles chapter of COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics)—a prostitute's rights organization. She's also the founder and president of the non-profit, educational resource corporation, ISWFACE(International Sex Worker Foundation for Art, Culture, and Education; pronounced "iceface"). The foundation recently placed a down payment on the historic "Wild West" Dumas Brothel in Butte, Montana to house the art and to serve as a cultural center and museum. "The Brothel gives ISWFACE a physical embodiment," she explains. Amoung the many historical items found in the brothel was a vintage postcard with a condom attached. Copies of the postcard will be distributed to health service agencies, family planning organizations and AIDS-awareness programs. Last year, Almodovar was a delegate to the World AIDS Conference in Geneva. She participated in a sex workers and AIDS panel. "In developing countries where they do not have access to a lot of information or condoms, what we and other sex workers around the world are trying to do for our peers is to give them the same access of information about safe sex and condoms that we have. In developing countries where prostitution is illegal, condoms cost as much as you make in a week. So then the sex workers are further put at tisk becasue they don't have the same access that other people do to condoms and safe sex information." Almodovar will attend the World AIDS Conference in South Africa in 2000.

Norma Jean Wright (Almodovar is from her first marriage), forty-eight, was born in Binghamton, New York where she was the eldest daughter in a family of eight boys and six girls. Her mother is a direct descendent of John Howland, a pilgrim on the Mayflower, and the Reverend Charles Chauncey, President of Harvard from 1654 to 1672. The Chauncey family traces its roots back to King Henry I of France. "On my mother's side she had all this blue blood, then she married my father and, of course, my mother's family was not very happy with that," Almodovar says referring to her father's lifetime occupation as a factory worker. She is close to her mother who is a fundamentalist Christian. "Her attitude is one that I rarely see exhibited by Christians, which is, that it is not her job to judge. That's God's job. She feels that people really need to look at people as individuals and not as a prostitue or whatever—a human being first." Newly released from prison, Almodovar appeared with her mother on The Sally Jessy Raphael Show. Sally asked her mother, "How does it feel? Your daughter's a whore." Her mother's response was, "Well, she hadn't made any worse choices than my other children." What was it like for Almodovar in prison? "It was very rough," she says. "Particularly the first time, the fifty days in solitary confinement. All I could think was it just made me more determined to change the laws. More determined to be an activist. In a free country these kinds of things should not be done to someone like me. I had not hurt anyone. I had not threatened anyone. My crime was that I tried to fulfill my friend's sexual fantasy. There were words that included sex and money—period. Those words are a felony pandering crime and for those words the law says you must go to prison for three to six years on the first offense with no prior convictions. If you commit rape, robbery, assault, mayhem, and murder and you don't use a gun you can get probation. I find it offensive that people don't get angry and say, "Excuse me. What on earth are we doing?" Almodovar's activism has come with a price. "The more involved you become as an activist, the less money you have (royalties from her book went toward legal fees), and being an activist takes all your time," she says crossing her legs as she drinks her ginger ale. "I have put my husband and myself in a position where we are impoverished through my bullheadedness," she pauses briefly and laughs, "but he still stands beside me and says, 'whatever you want to do. You believe in what you're doing, so go for it.'" Almodovar has appeared on over 500 television and radio shows including 60 Minutes, 20/20, The Joan Rivers Show, and A&E's American Justice. As Almodovar gained more celebrity, she phased out her sex work. "The more high profile I was, the less my clients wanted to see me. Because they didn't need to be associated with someone who could get them arrested or at least questioned. When my OGs (original guys) stopped calling that was that." In 1995, Almodovar was an official delegate to the UN Fourth World Women's Conference in Beijing, which concluded that "all prostitution and pornography are incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person and must be eliminated." Almodovar finds this position irrational. "Now, I happen to be a woman. I happen to be a prostitute. I happen not to feel that my work is incompatible with my dignity and worth. I happen to feel that being arrested and going to jail isn't compatible with my dignity and worth. We're out there alone saying, 'you understand that we are all in this together.' And we will make so much more progress if you will not treat us like illegitimate stepchildren." Almodovar says that when people discuss prostitution, they get emotional, opinions fly, and they usually conclude that prostitution is degrading or dehumanizing. "These are all concepts that are subjective in nature," she says. "And for someone who has not been a prostitute, who has not experienced what I have experienced, to tell me what my experience was like, it's so offensive. Until prostitution is accepted as a profession so that we are in the arena where we can deal with the issue of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases on a basis where the gay community can, then it's going to be a terrible problem for sex workers in developing countries as it is now because they just don't have a platform to talk about this." Sex workers, like people infected with HIV, are not disposable people, says Almodovar. "We are so stigmatized. If they can see us as human beings maybe they will get upset when they know that we are treated this way. (She says an unofficial police term for murders of prostitutes, transients, and homeless people is NHI—no humans involved.) If they know that we have lives and family and that we're not all strung out on drugs and out on the street corner and therefore considered disposable people. If they can see that, maybe, maybe things will change for us. As Steve Forbes says about the abortion issue, 'You have to change the culture before you can change the law.'" VH-I recently produced a piece about ISWFACE that featured Almodovar. We trek upstairs into her neatly cramped office to view portions of the show on video. As we climb the stairs, Almodovar turns more lighthearted. "Most people don't know that the Statue of Liberty, the United States symbol, the model for that was a French prostitute. That's my culture," she says. She catches my surprise at this and responds. "You think they're going to tell you in school that the model for the symbol of freedom was a whore. I don't think so!" she says with an inflected rise in her voice, letting out a loud, "Ha!" She continues, "The models for all of the paintings that hang in the Vatican and everywhere else were all Courtesans."

After the video, Almodovar calls up on her computer the cartoons she created while in prison. They will be included in her next book, Pros and Cons: Postcards from Prison. Next, she brings out an overstuffed scrapbook that holds many of the items that she uncovered at the Dumas Brothel. The artifacts include earrings, lighters, perfume bottles, pornographic photos from the turn of the century, and many other varied paraphernalia. Hairs on my neck bristle when she shows one of the girl's keepsakes. Tucked inside a petite silk purse is a metal Kellogg's Drinket can from the twenties with the remains of a pet—a yellow canary. Near the back of the book is the vintage condom postcard. She gingerly pulls it out of its protective plastic. Reproductions of the postcard will be used in an AIDS prevention campaign. "I have a friend who manufactures condoms, and I have another friend who manufactures postcards. Obviously you won't be able to use the condom that's on the postcard, so we'll have another condom that's sealed in a package that people can use. We're going to sell them in stores. We're going to distribute them freely to different organizations," she says. She leans back, shines a confident smile, and concludes. "They're going to go all around the world." She means it. |